How Horses Learn, with Debbie Busby, Clinical Equine Behaviourist

Why is it important to understand how horses learn?

This weeks Blog is written by Debbie Busby, Clinical Equine Behaviourist and is an interesting insight into the ways that horses learn and ways that we can help our horses to learn! Debbie is one of the guest experts in my Strength & Straightness Programme and is joining us live this month...details below!

How do horses learn to do what we want them to do? We can understand this by exploring psychological learning theory. It’s important to understand how horses learn, because in our interactions with horses we’re always trying to get them to do things that they might not naturally prefer to do, at the times when we want them to do those things, so if we want to enjoy our horses, it’s useful to know how to achieve that, in humane, ethical ways that follow correct psychological principles. I’ll explain some of these principles below, and hopefully they will help you in your training and riding.

Habituation – getting used to things

Habituation is the simplest form of learning and means that the horse avoids wasting energy on insignificant events. As a result of habituation the horse becomes less reactive to the things they encounter (stimuli), and the innate startle response wanes after repeated presentations of a stimulus that could be potentially threatening – the horse learns to ignore the stimulus, because there is no associated reinforcement or punishment.

A classic example was described in Anna Sewell’s famous book, where Black Beauty was initially frightened or ‘spooked’ by the sound of the trains going past. However, as long as he could run away to a safe distance, then over time he got used to (habituated to) the trains.

We must habituate our horses to any new stimulus gradually, so that they don’t become sensitised.

Sensitisation – getting worried about

In contrast to habituation, through sensitisation a horse will become increasingly reactive to an object, event or an experience. The evolutionary function is to ensure the horse notices and reacts to something that may potentially threaten their health or survival. In the above train example, if Black Beauty could not run to safe distance, he would have become sensitised to trains and his fear response would increase rather than decrease. Sensitisation is the start of the development of a “flighty” or “spooky” horse.

Operant conditioning – learning from consequences

Through the psychological process of operant conditioning the horse learns that there are consequences to the behaviour they perform.

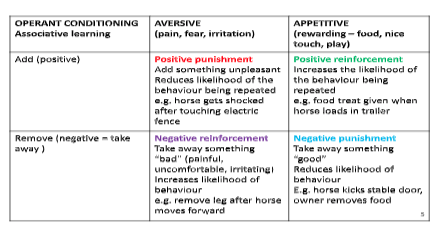

In operant conditioning, it matters whether the stimulus is “good” (“appetitive” e.g. food, scratches) or “bad” (“aversive” e.g. painful, confusing, frustrating). The terms positive or negative are mathematical terms that relate to whether something is added or taken away. So in negative reinforcement a rider adds uncomfortable or annoying leg pressure until a horse moves forward, and then the rider remove that pressure. In positive reinforcement a trainer would add a food reward after a desired behaviour had been performed, such as giving food when a horse walked calmly into a trailer.

In operant conditioning we also consider the effect on the horse’s behaviour: does the behaviour increase or decrease? Reinforcement, whether positive (adding something pleasant) or negative (removing something unpleasant), strengthens behaviour. Conversely, both the punishment quadrants (positive punishment: adding something unpleasant, or negative punishment: removing something pleasant) are likely to decrease behaviour, for example the behaviour of touching an electric fence is followed by an unpleasant shock, and as a result, the horse is less likely to touch the fence in the future. Or a feed bucket is withheld until the horse stops kicking the stable door.

Classical conditioning – learning by pairing

In classical conditioning, learning takes place by pairing two stimuli or events. A neutral stimulus (NS) becomes associated with an unconditioned stimulus (US). The unconditioned response (UR) is expressed in response to the unconditioned stimulus (US). With repeated pairing, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS) that triggers a conditioned response (CR), even in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, a fly spray bottle (neutral stimulus) means nothing to a horse at first, but after hearing a few hissing (spray) sounds (unconditioned stimulus – might be a snake!), the horse becomes fearful and tries to escape (unconditioned response). The result is that the horse then shows a conditioned, avoidant response to the bottle (now a conditioned stimulus) as soon as it is picked up, even before they hear a hissing sound.

In another, ridden, example, the rider applies their leg (initially a neutral stimulus) to the horse’s side. The horse feels uncomfortable pressure (unconditioned stimulus) and their unconditioned response is to move away from the pressure. Over time and with repetition, the rider’s leg then becomes the conditioned stimulus, and, if the training is done well, the horse will continue to express the conditioned response of: move off the leg, without the rider needing to escalate any pressure.

Making learning easy

Understanding the principles of learning theory helps us to be careful what we’re training, because our horses are always forming emotional (conditioned) responses to what we do with them; they’re experiencing everything as either “good” or “bad” in one way or another, and it’s up to us to maximise the good experiences and minimise the “less good” ones, in order for learning to be effective. We can look at this balance of good and less good experiences as “the behaviour bank account”, and it needs to be in a good credit position!

If you need any support in helping your horse to learn, and you have a calm, relaxed horse who just can’t seem to “get” what you’re trying to explain, a reputable trainer or coach who understands learning theory will be a good start. If your horse’s emotions are getting in the way of learning, and you’re seeing behaviours such as spooking, napping, rearing, bucking or bolting, a properly qualified clinical behaviourist will be able to help you.

Contact Debbie for more information at [email protected]

Written by Debbie Busby, Clinical Equine Behaviourist

Website: Debbie Busby, Evolution Equine

Facebook: Debbie Busby, Evolution Equine Behaviour

***Debbie is one of the guest experts in my Strength & Straightness Programme; if you would like to learn more about Equine Behaviour, you can join my members group to access Debbies training modules and join her live session in the group this month! Click here for more details...: Strength & Straightness Online Programme